Battlelands, a solo exhibition of film, photography and sculpture at White Rainbow, Fitzrovia, London by Japanese artist and filmmaker Meiro Koizumi (b. 1976, Gunma, Japan). The artist’s first UK solo exhibition.

In his compelling and challenging body of work, Koizumi examines a range of complex issues: power dynamics on scales both familial and national; the tension between staged and authentic emotion; and the conflict between duty and desire. Koizumi’s artistic practice is shaped by and often directly addresses the political and military history of his native Japan, and its impact on culture and society in the present. Japan’s Peacetime Constitution – a reaction against the brutal militarism of Japanese imperialism – has seen pacifism become central to Japanese identity. Yet the imagery of war looms large over the Japanese psyche today, with on-going debates in the media over how long the peacetime order will hold. This is the context in which Koizumi has worked for the last ten years.

In Koizumi’s provocative performances and constructed scenarios, the artist employs techniques of disruption, repetition and manipulation of his subjects to create extreme emotional reactions. Koizumi intervenes in his works whether directly or indirectly to reveal the fragility of the human psyche and the multi-layered relationships between the voices of power and the multitude or the individual, challenging conventional and official accounts.

At the centre of Koizumi’s white rainbow exhibition is Battlelands (2018): an expansive new body of work four years in the making, which developed on from the artist’s work surrounding the history of Kamikaze pilots and the psychology behind such radical action. Spanning a new single-channel film and still photography, the project sees Koizumi work for the first time with non-Japanese subjects, engaging United States veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Five veterans recount traumatic experiences during these past military conflicts, while wearing body-cams that record images of their current domestic spaces and landscapes in the US. Koizumi seeks to capture banal and ordinary images from his subjects’ daily lives, attempting to construct another kind of image of war. The work articulates how traumatic memories of conflict impact the everyday for these individuals.

The soldiers interviewed came of age at the time of 9/11, and all strongly believed in the political justification for the wars they fought in. As Dave Grossman notes in his book On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, only 2% of soldiers feel no guilt after killing an enemy combatant. Battlelands looks at the long-term consequence of warfare: how the experience of being on the battlefield involves putting one’s body in a space outside of our ‘normal moral system’, as the artist has stated. Consequently, many veterans suffer in the transition from the reality of war to civilian life, which can lead to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PSTD), whether diagnosed or not. For Koizumi, video is most able to articulate these veterans’ lives, as it can: ‘represent the complexity of multi-layered physiological states in tangible form.’ The film recasts the imagery of a soldier from visions of heroism in popular culture into a more vulnerable portrait of a civilian living with past horrors.

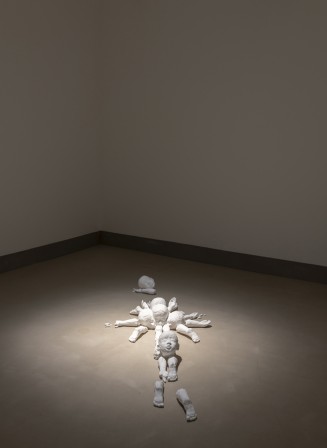

A sense of dread suffuses the lone work installed in White Rainbow’s smaller gallery space. Sleeping Boy (2015) is a rare foray into sculpture for Koizumi, which was made following the birth of the artist’s son. Just as the threat of flashbacks haunt the military veterans, Koizumi was plagued by fear of his son dying. He realised he had a primal instinct to protect his son. To deal with his anxiety, every night Koizumi copied the shape of his son’s head, hands, and feet, subsequently producing a clay sculpture.

For Koizumi, medals are the only way to celebrate military personnel, which in turn value heroism, bravery and sacrifice. What goes unrewarded is the struggle with weakness and vulnerability after the fact. Koizumi tries to redress this here in his poetic portrait of military veterans, and in his own deep psychological fears surrounding the safety of his family.

The exhibition ran from 22 November 2018 – 12 January 2019. The accompanying catalogue on Meiro Koizumi includes essays by Dr Isobel Harbison an in-conversation between Meiro Koizumi and Jason Waite, and installation photographs.