An ongoing endeavour Conversations, a series of research-related interviews with curators, artists and academics.

Read More

An ongoing endeavour Conversations, a series of research-related interviews with curators, artists and academics.

Read More

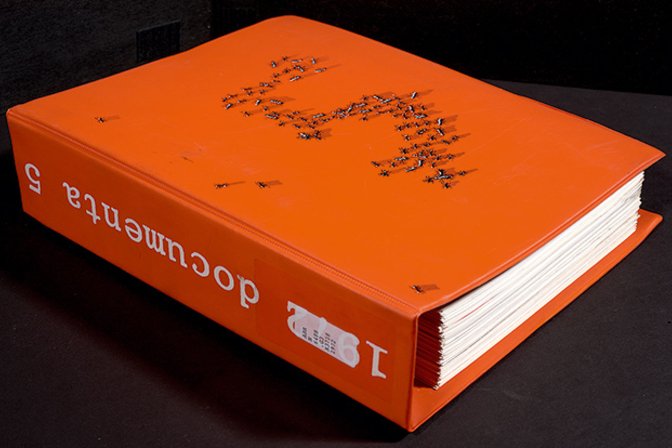

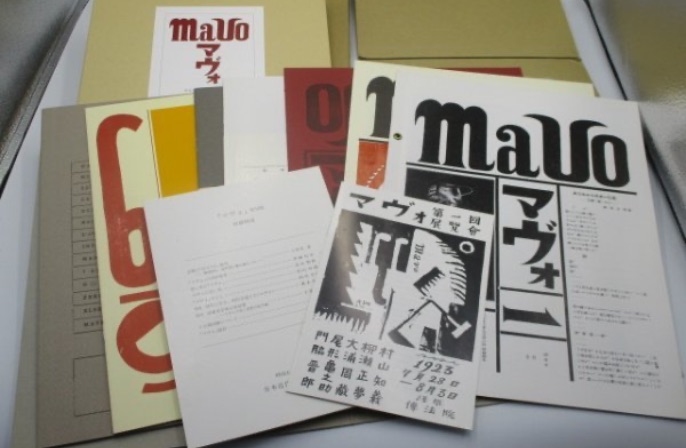

Qualitative, descriptive and comparative research based publications – a collating of research, and critical overview of the knowledge.

Read More

Talks examine the structure and characteristics of art and culture. Offering a broad, comparative perspective that takes into account global and regional contexts.

Read More

Lectures on Modern and Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, London and other institutions focus on a number of interrelated themes.

Read More

Bringing together research specialists and international scholars from various disciplines through symposia, seminars, workshops and lectures in Japan and UK.

Read More

Research as a fellow at Japan Foundation and at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London.

Read More

An essential accompaniment to research, commissioning and exhibition activities, projects and events.

Read More